Flamboyant, daring and diverse, it’s now 40 years since the Derry senior football team of the mid-70’s achieved back to back provincial crowns in a decade of global change. A talented midfielder on those teams and a winner of three Ulster senior titles, Tom McGuinness speaks about growing up in Derry’s Bogside, his continued admiration for his former team-mates and what the future holds for the GAA in his city.

*****

Looking back there’s always a moment; a tiny snapshot in time which, in hindsight, helps us to rationalise an event, or series of events, and thus create some essential order. They’re the jewels that sports writers constantly crave to try and make sense of what it is they have witnessed, and to relay the narrative – the game-changer, the pivotal moment, the talking point.

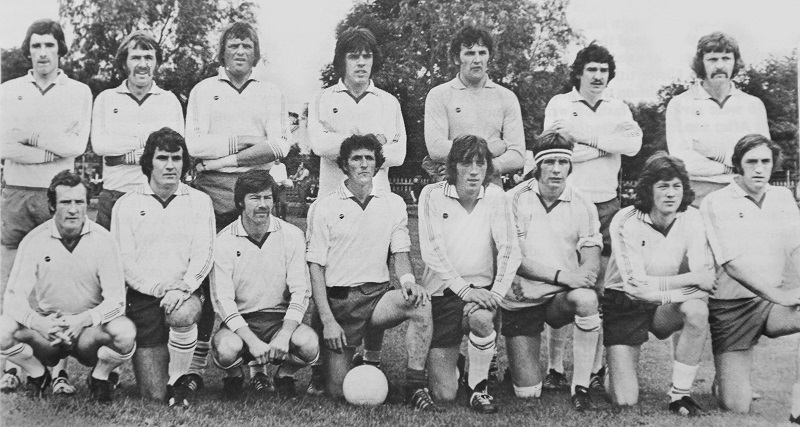

It’s now forty years this July since Derry’s back-to-back Ulster senior football titles in 1975 and 1976. Though the years have been and gone, there’s still one moment of the epic replayed Ulster final of ’76 against Cavan – the undisputed free-playing kings of Ulster football in the first half of the 20th century – which vividly stands out in the mind’s eye of the team’s midfielder, Tom McGuinness.

“I remember laying a ball off to Mickey Lynch and just watching him power up the field past Cavan players. It looked so easy for him. He was so powerful and I remember thinking ‘we are going to win this game.’”

And that they did, emerging victorious by 0-22 to 1-16 after extra-time. It was a momentous achievement and a record which stood in the province until the Tyrone double twenty years later.

Four decades haven’t diminished McGuinness’s Clones memories or a single strand of his support for the Derry senior football team. Living just around the corner, he’s a man to rarely miss a beat at Celtic Park, and he recalls games of forty years ago with equal clarity to those of a few months ago.

“I have great memories of that period (1975-76),” he proclaims with a characteristic sincerity. “There were some serious footballers about that team. Gerry McElhinney and Mickey Lynch were great attacking players and then you had Anthony McGurk at the heart of it with fellas like Mickey Moran, Peter Stevenson, Tom Quinn and Brendan Kelly.”

‘At the heart of it’… it is a telling phrase which gives some insight into McGuinness’s relationship with the Lavey man, who was a rock and one of the key generals among the Derry team of the mid-70’s. It’s a friendship which also saw McGuinness play a management role at Steelstown – a club which was one of McGurk’s great passions after his playing days and which is now a shining light in the GAA’s pathway for development within the county.

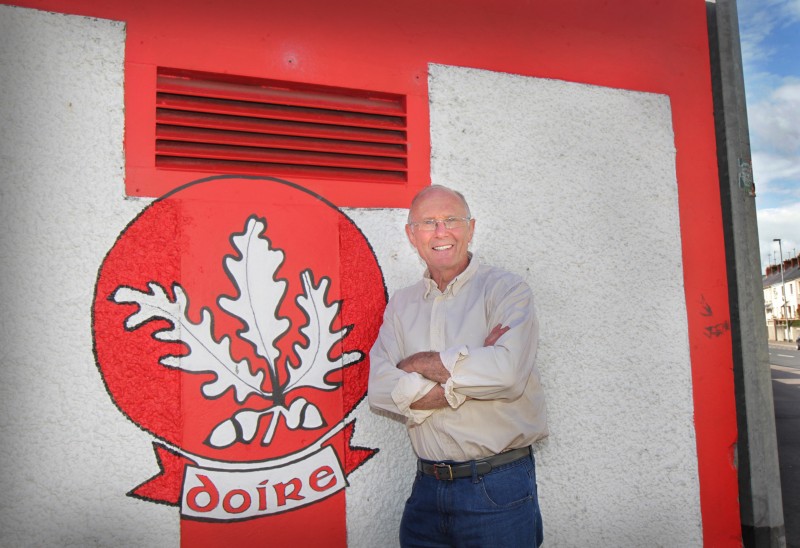

A former Doire Colmcille player, a club previously known as Sarsfields, Tom McGuinness’s past and present has always been GAA and always Derry.

“I look at Mark Lynch now,” says McGuinness. “And I just see Mickey, both great players, and players you just want to give the freedom to play.”

*****

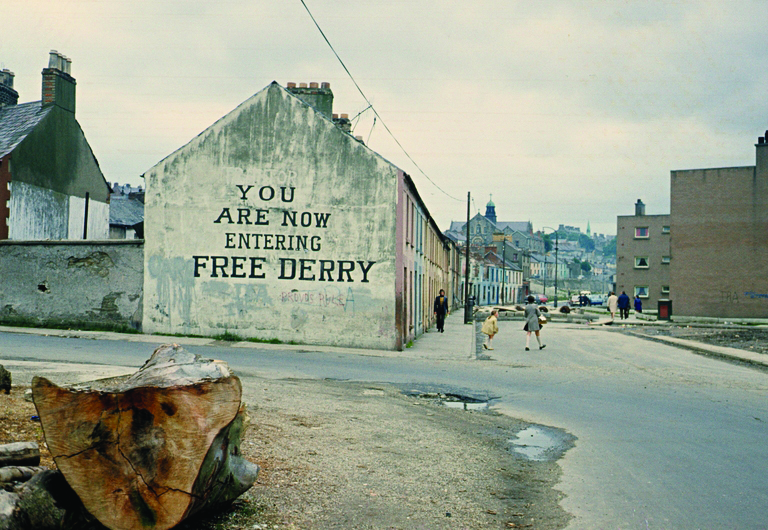

‘YOU ARE NOW ENTERING FREE DERRY’ reads the famous black lettering on the white gable – all that remains of the now demolished row of terraced houses on the city’s Lecky Road.

Known as Free Derry Corner, it’s an iconic sight and one that has been seen on TV screens all over the world, often in the context of civil strife, but always a focal point for the local community.

With Donegal at its back, the city walls and the River Foyle to its front, the Bogside community is one in which Tom McGuinness was born, raised and still remains. The eldest in a family of seven children, the former Derry midfielder comes from an eclectic generation of people and personalities which includes Eamonn McCann, Nell McCafferty, Phil Coulter, John Hume, Dana Rosemary Scallon, Paddy ‘Bogside’ Doherty and, of course, Tom’s younger brother, Martin.

‘Well, as Kavanagh said, we have lived. In important places,’ wrote Seamus Heaney in ‘The Ministry of Fear’, a poem dedicated to another Bogside man, Seamus Deane, author of perhaps the best known literary work about the area and its community in the middle decades of the twentieth century; ‘Reading in the Dark’. In light of the personnel involved and the times now gone, the quip seems somewhat apt.

Seamus Deane’s uncle, Phonsie, Derry GAA secretary from 1952-1964, forms part of a band of people such as Tommy Mellon, John McCrystal and Barney McFadden, who have strived through the hard times to promote and foster Gaelic games in the county’s largest urban centre.

“There have always been a hard core of dedicated people in the city, people like Seán Moynihan and Seamus McGilloway, who have worked hard to keep Gaelic games alive in the city. But it’s definitely hard in somewhere the size of Derry,” explains McGuinness.

It’s a subject close to his heart.

Margaret McLaughlin

Schooling at Brow o’ the Hill CBS, later St Peter’s, the now closed institution was McGuinness’s first real introduction to Gaelic games:

“I learnt the basics at the Christian Brothers School – you had men like Brother Egan, Brother Gibbon, Brother Connolly and Brother Lynam who were very serious about their GAA and they gave me a good grounding in it.”

“The same would have been true of St Columb’s College where there was a big emphasis on Gaelic football, and you would have had boys like Tony ‘Doc’ O’Doherty and Johnny ‘Doc’ – a brother of Paddy Bogside – who developed into great Gaelic footballers. But for me it was at the CBS where I learned my football,” he says.

Winner of an All-Ireland U21 medal with Derry in 1968, and also named on the Irish News’ ‘Pick of the Mighty Oaks’ 125th anniversary of the GAA selection, Tom McGuinness was described as ‘the best fielder of a ball since Jim McKeever’, an attribute he puts down to another sporting discipline:

“I took to it fairly easily,” he says of Gaelic football. “I was an athlete. People would have said that I had no feet,” he laughs, “but I had the fitness and the speed. I was a pole-vaulter, and that strength would have helped me where I played in midfield.”

The role of the CBS in McGuinness’ Gaelic football career cannot be understated. Nor can the role of happenings at St Columb’s, where under the guidance of former Fermanagh player, Fr Ignatius McQuillan, and Kerry man Seán Moynihan, a revolution in Derry football began with the county’s first Hogan Cup victory in 1965. School boy players such as Colum P Mullan, Chris Brown, Tom Quinn, Malachy McAfee, Seamus Lagan, Barney Mullan and Peter Stevenson would become vital lynch-pins in the future of Derry teams which began with the county’s first All-Ireland minor title in 1965, the U21 title of ’68 and eventually three Ulster senior titles (1970, 1975 and 1976), with McGuinness playing a part in all three.

Tom McGuinness may be the last Derry City man to win an UIster senior football medal but he wasn’t alone.

“I wasn’t the only man Colmcille had on the squad. Both Mark McFeely and Johnny O’Leary were part of it,” he says. The immediate positioning of his former team-mates into the equation speaks volumes about McGuinness’s character. The success of others is genuinely welcomed.

Johnny O’Leary, whose father was a bank manager who relocated north to Derry City from Waterford, joined the ranks at St. Columb’s, and with his natural passion for Gaelic game, fitted right into a year-group of boys awash with the subject.

“That team was managed by Frankie Kearney and Seán O’Connell, with Seamus Kelly from Ballinascreen and Liam Hinphey,” explains McGuinness. “They would have given us great confidence, with one of things which sticks being that Seán O’Connell was great trainer. There was always something different going on at training,” he says energetically.

It’s an interesting angle.

As the late, great Muhammad Ali once declared: “The fight is won or lost far away from witnesses – behind the lines, in the gym, and out there on the road, long before I dance under those lights.”

Gaelic games are no different from other sporting disciplines. Preparations are key, and were just as vital forty years ago as they are in today’s game. However, these weren’t ordinary times behind the lines. Or on the roads.

Still, the dance went on.

LAST FOUR

If you perform a search on YouTube for ‘Gerry McElhinney 1975’, there’s a wonderful piece of old film of the young Banagher man, Björn Borg-esque with a brilliant white head band curtailing a mop of long brown hair, cutting a dash through the flailing Dublin rear-guard to score a point in the All-Ireland semi-final of that year.

After he scores, McElhinney, running back out the field, pulls up his shirt, and seems be to in some pain.

In hindsight, it’s hardly surprising. Shipping challenge after challenge, one of the belts cracked the Derry man’s ribs. Oblivious to the nature of the injury, McElhinney played on, contributing heroically to what ended in a five-point defeat.

After needing a replay to get past Monaghan in the Ulster semi-final, the Derry team of 1975 had been imperious in the Ulster final defeating Down by 1-16 to 2-6 in a display that helped garner All-Stars for Anthony McGurk, Peter Stevenson and Gerry McElhinney. Defeat to Dublin in the semi-final proved to be a reality check in terms of tactics and conditioning though.

However, this was only football.

Events would take on an altogether more sinister turn with the targeting and assassination of Bellaghy man, Colm McCartney (22) and his friend and work colleague, Seán Farmer (32) from Moy, Co Tyrone as they returned from the game in Croke Park. Reportedly stopped at a “UDR” checkpoint on the Newtownhamilton-Castleblaney Road, the two men were abducted and shot.

‘Death on a County Road’ by Desmond Fahy contains a vivid and haunting account of the events of the evening of 24 August 1975 and their background, which were among the first overt targeting of the GAA community of the time, circumstances into which all analysis of northern GAA at the time have to be placed. The security situation had already meant restrictions on the number of training sessions which could take place, particularly for inter-county teams where travel was an essential element. And with the targeting of GAA supporters – the interpretation of the time being to prevent travel to matches, particularly in the south – the combined package served to introduce a glass ceiling for affected counties; a barrier not broken until Down book-ended the period in 1991 having also been the first of the six counties to take Sam Maguire back over the border in the 60’s.

Having returned from Dublin and regrouped soon after in 1975, the Derry players refocused their efforts for the following year, reaching the National League final of 1976 – this time being edged out by Dublin in a thriller by a single point. However, league performances, as so often happens, proved to be a false dawn as after those titanic struggles with the Breffni which saw Derry reclaim the Anglo-Celt, their All-Ireland ambitions were abruptly halted by Kerry’s golden generation, who are now known to have trained 4-5 times per week.

“We got an absolute hammering by Kerry in the 1976 All-Ireland semi-final,” recalls McGuinness. “They were a great team; Mikey Sheehy, Pat Spillane and John Egan, but that was an awful experience. We came up against them and the great Dublin team of that era with Mullins, O’Toole, Hanahoe and we were very unlucky to lose to Dublin in the National League final in 1976. Those were two serious teams.

“I think they were ahead of the rest of the country in terms of their tactics. People talk about the game being very tactical these days but that’s when that all started. They were a bit better drilled than the rest of the teams in the country.”

It all leaves so many questions, ifs and regrets. Kearney and O’Connell were certainly innovators but had the golden generation of players of which McGuinness was a key member been afforded the same freedoms to train beyond their once a week gathering, which in itself required a large degree of organisation and planning in the climate at the time, would they have gotten over the line?

Who knows? It’s all history now. What we can say for sure is that the legacy of McGuinness, McGurk, O’Connell, Stevenson and others lived on in future generations.

“There was a romance and flamboyance about those teams of the seventies. They caught our imagination” declared Henry Downey at a night of celebration for 125 years of Derry GAA in May 2013.

FOCAL POINTS

“In the county, in places like Ballinderry and Banagher, the GAA club is the community. That sense of ‘the GAA club being the focal point’ is harder to achieve in the city,” explains Tom McGuinness when asked for his thoughts on development of the GAA in the city. “You have other distractions such as soccer and it’s harder to keep people on board.”

For a town which has seen massive changes over the past decade, the sight and sounds of an Irish President addressing a GAA Congress for the first time in the association’s history was made even more poignant by where he stood. Ebrington Square, now a public place on the banks of the Foyle was once a British Army Barracks. However, on Saturday 23 March 2013 it was the centre of the GAA universe as far as Gaels were concerned, with President Higgins declaring:

“The GAA in Derry has been playing its own important and central role within its many individual communities for almost one hundred and thirty years now, creating numerous memories and weaving itself into the history of Derry towns and villages and the annals of many family lives,” before continuing:

“The sense of renewed optimism and community solidarity, which is now so palpable in this City, is a transformation in which the Derry GAA has played no small part.”

The president’s words – spoken from the congress stage on the east bank of the Foyle while facing west, and in a year which saw the national Féile and national Scór finals come to the city and county – may seem merely aspirational when it comes to the GAA in Derry’s largest urban centre. However, the evidence on the ground in the past three years has both reflected and echoed his sentiments and those of Tom McGuinness.

With almost three million pounds invested into capital projects over recent years in Seán Dolans (£800k), Doire Colmcille (£750k), Na Magha (£700k) and Doire Trasna (£750k), the city’s core infrastructure is taking shape and it’s something in which Tom McGuinness takes great pride:

“The clubs having their own grounds will definitely help – it’s great to see Colmcille and the likes of Steelstown and Na Magha in the hurling with their own grounds. It takes time, but it will definitely help give those clubs a sense of identity.”

Margaret McLaughlin

With six full or part-time Games Promotion Officers now dedicated to fostering a positive experience of Gaelic games for primary school children, McGuinness is hopeful that his record of being the last city man to hold an Ulster senior medal is well on the way to being history:

“There have always been a few players from the city who have made the breakthrough, you’ve Neil Forester on the current squad, Paul O’Hea won an All-Ireland minor and Emmett McGilloway won an all-Ireland Under 21 back in the 1990s. It would be great to see some more making the breakthrough.”

As anyone with knowledge of how the GAA works will testify, when you have communities established with Gaelic grounds at their focal point, you have a fighting chance.

After a lifetime of immersion in it, the Gaelic identity and self-help community-based ethos it requires to flourish isn’t something Tom McGuinness has ever struggled to get to grips with. That’s not to say that he doesn’t still have his own personal battles with it though.

“I find it hard to watch matches these days,” he reveals. “It’s very hard watching from the stand because I have this constant feeling that I just want to play.”

Comments