Still only a teenager when he scored a goal and six points in the All-Ireland club final of 1991, Brian McCormick was an integral part of one of the greatest Derry club teams of all time…

***********

The legendary stories surrounding Matt ‘Sonny’ McCann are plentiful. They are part of Derry’s footballing gospel. Like the fact that Sonny – centre half back on Derry’s first national title winning team of 1947 – would put matchboxes on the crossbar of the goals and strike balls at them from fourteen metres until they were all obliterated. Or the time at a drenched Magherafelt county grounds, with a pigskin ball so laden with water that it must have weighed half a stone, that Sonny reportedly struck a long range free kick so hard that it cleared not only the crossbar but also the adjoining main road, landing in the graveyard opposite and smashing a headstone in the process.

“That definitely sounds true,” laughs Brian McCormick, a grand nephew of McCann. “The urban myth is hard to beat, especially when there’s no video evidence!” he chuckles.

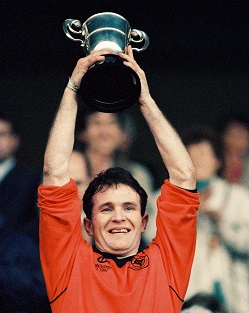

It’s hard to believe that it’s now twenty-five years since McCormick wrote his own chapter into Gaelic football’s lore. Having just turned nineteen, and in his debut season as a senior footballer, Brian McCormick coolly struck a goal and six points for Lavey in the All-Ireland club final of 1991.

Luckily videos of McCormick’s feats do exist, not that he watches them.

“I’ve seen bits and pieces of that game but haven’t ever sat down to watch the full thing. I don’t actually recall too much about the games we played to be honest,” he explains. “I only ever remember the bits I’ve seen played back on video, if that makes sense.”

TEN DAYS

Lavey’s march to ultimate glory in 1991 was truly remarkable, imprinting itself onto the psyche of the players who took part, as well as their peers. But for McCormick, one of the brightest and youngest stars to shine in that ten game campaign, it was nearly the St Patrick’s Day joy which wasn’t.

“I was actually due to go to Australia in January of that year,” begins McCormick. “I had been out for ten days in July time for a trial with the Melbourne Demons. They had offered me a two year contract due to start in January of 1991 but I turned it down, I think, in September of 1990.”

With Conor Glass the most recent Oak Leaf recruit to the rookie ranks of the AFL, it was Anthony Tohill who had been the pioneer explorer down under. McCormick almost wasn’t far behind.

“Anthony had been out there nine or ten months,” McCormick recalls of his former St Pat’s Maghera teammate. “To be honest, Australia just wasn’t for me. I didn’t click with the place. I always said that if I had been given the same opportunity in America, I’d have taken it.

“The minute I went there, I liked the country, liked the people, whereas, for some reason Australia just didn’t sit well with me. That was a snap judgement I suppose, made in ten days. Anthony told me that they actually couldn’t believe that I had turned it down.”

It turned out to be a wise move, in more ways than one.

Accompanied in an AFL draft pack by Derek Duggan (Roscommon), John Hegarty (Cork) and Niall Buckley (Kildare), McCormick’s decision to pull the pin after only ten days seemed a prudent call after Tohill and Buckley’s contracts were terminated.

“I would have gone in January, missed the All-Ireland and had my contract terminated by the end of April because they said they just ran out of money. You’d have thought they’d have a bit more foresight and planning than that, but that was the story they came up with anyway.

“I’ve never looked back and said ‘I wish I had gone to Australia’. From the minute I made the decision, I was happy with it,” he declares.

TEN GAMES

Gilbert Enoka is the man credited with introducing the ‘no d*ckheads’ policy to the New Zealand All-Blacks. Now much documented, it’s a group statement of intent where each player would demonstrate their humility by, among other things, sweeping out the changing rooms after training or a game. The mental resolve now associated with the best Rugby team on the planet is something that Enoka worked on at an individual level with each player. If, during a game, they felt their focus wandering from the task at hand, or the mental pressure building to the extent that it affected the mechanics of their given role, they were each given mental lifebuoys back to shore. Richie McCaw, for example, would rhythmically stamp his feet to reboot his mind. Brad Thorn, the six foot five lock, would douse himself in water to reset his thinking whilst number eight, Kieran Read, would pick a single point in the stadium and focus his gaze until he felt his mental sharpness return.

But when Brian McCormick’s gaze was drawn to a point on an almost empty Hill 16 during the ’91 club final, his thought process was momentarily perturbed.

“Jesus Christ, that’s Seán Convery,” he laughs, recalling what was going through his head. Convery and one other were the sole occupants of the famous Croke Park terrace and with ‘a hip-flask on board’ were ‘happy as Larry’.

“My mind was elsewhere for a second,” says McCormick.

Sportsfile

Much has made of the occasion surrounding an All-Ireland final where the game itself can become something of a sideshow. Emotional energy can become a drain on a body’s ability to perform to its maximum level.

“The standout memory I have about the All-Ireland final was the unbelievably relaxed attitude within our dressing room,” says McCormick. “The day before the game, the evening before the match, the morning of the game and even going into Croke Park – everybody was unbelievably relaxed to the point where a couple of men, who shall remain nameless, went into the Brazen Head in Dublin for a few pints the night before the final,” he reveals, smiling mischievously.

An encounter with a reporter from the Irish Independent, who made his way to the foyer of the team hotel on the morning of the game revealed more about the build-up to the Croke Park showdown.

“He says: ‘Have you been for your warm up, lads?’ recalls McCormick.

“I think it was one of the McGurks who looked at him and shrugged, saying: “No, we never do a warm up.”

“He (the reporter) was completely dumbfounded and you could see it in his face. He was thinking ‘yeah, these boys are only here for a jolly and they’re going to get tanked.’”.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Entering the ground and changing rooms, the spirits among the Lavey team were still high and the mood relaxed. Nervous anticipation was nowhere to be found according to McCormick, who at a young nineteen must surely have been on the journey of his life. Even a delay to the start of the game failed to raise the expected butterflies.

“I don’t know if it [the delay] affected Salthill or not,” ponders McCormick.

“We hadn’t left the dressing room with fire and brimstone. There was no ”Let’s go and kill dead things’ attitude. It was like this was what was expected of us, so let’s just go and do it. There was no question of it not happening,” he states, before summarising: “It certainly wasn’t arrogance. It was a relaxed confidence and it nearly felt inevitable that we were going to do it.”

With the Galway men registering the opening scoring, the rhythm entered Lavey’s game following a clever dispossession of the Salthill number three by full forward, Seamus Downey. With the ball transferred quickly to the left, Don Mulholland calmly strode forward, and with head down, planted the ball in the Canal End net. It was a text-book finish and just the tonic the Ulster champions needed, and expected.

Sportsfile

“Seamus Downey used to do this thing at the start of a game where I would go into full forward and he’d come out to centre half forward,” says McCormick. “Then, after twenty seconds, we’d change again.

“To this day, I don’t know what he was at or why,” he laughs. “But I went along with it anyway and standing in at full forward, I looked at the Salthill full back and he was a beast of a man! He had the sleeves rolled up, biceps bulging and was breathing very heavily. I was glad to get out of there after twenty seconds. I made my way out and said ‘Well Jim, all the best with that.’ An hour with that boy wouldn’t have been a pleasant experience,” he laughs again.

However, Downey’s deftness had pickpocketed the big defender and Lavey were on course, building up a three point lead at the interval.

Brendan Regan pulled off a flying fingertip save from Mark Butler to deny them a goal,” McCormick recalls about the start of the second half. “It was a real game changer.”

Regan’s save, like Mulholland’s first half goal, put the Derry men back into the groove and McCormick’s left boot continued to register on the scoreboard. All that was required now was the killer blow, and it came from the nineteen-year-old at the second time of asking.

“I got a point before that (the goal), having been straight through on goals. If I had been more composed, it would have been a goal. The ball went off the outside of my foot and over the bar. The next chance, whatever way it came about, the keeper came out and got a foot to it, but I had kept it low this time and it went into the net. That one didn’t look as well as the previous glory effort for the top corner but it got the job done,” he says.

With five booming left boot strikes in the final, and a point from play just before the goal, McCormick’s deadly accuracy from all distances from the dead ball was one of the trademarks of that 90/91 Lavey campaign. Having started out casually as an arrangement between McCormick, Hugh Martin McGurk and John McGurk, as the year went on McCormick started taking the kicks which were awarded further and further to the right, away from the traditional area for a citog. There was an area, ‘about ten yards left of the posts’, where his domain ended and Johnny McGurk’s right boot took precedence, but it was McCormick’s contributions which made a lasting effect in people’s minds, and, more importantly, on the scoreboard.

“It literally was a purple patch which clicked for me at that time,” he says of his free-taking prowess. “I did work at it over that period though. At school Eamonn Burns would have spent hours taking frees. That was never my forte or something that I spent any time on at underage,” he explains.

“I actually never considered myself particularly good at it. It just happened to click during that particular period, and as quickly as it came, it left me.”

EAMONN

“MA-CORMAN-ICK” cackled Eamonn Coleman as he lent down across the table in the Imperial Hotel in Garvagh.

“Eamonn would use three syllables to address me,” smiles the Lavey man.

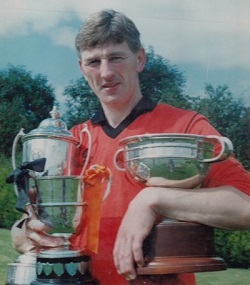

Having been drafted into the Derry senior panel following Lavey’s glorious seventeenth; Brian McCormick began a short, but highly charged, relationship with the legendary manager.

Colm McGurk’s goal for Derry in the opening round of the Ulster championship saw the Oak Leaf wrestle victory away from Tyrone in Omagh.

“I didn’t make the subs,” recalls McCormick”. “So I said ‘sod this, I can’t be bothered with this’. He left the panel. Call it cockiness, call it the folly of youth, call it whatever you wish, the 19-year-old had had high expectations but soon found out that county was a different game.

“He (Eamonn) didn’t bring me back in ’92. It was hardly surprising after the way I had carried on,” explains McCormick. “Then in ’93, he brought me in for the start of the year along with the rest of the Lavey players.

McCormick, along with Henry and Seamus Downey, and John and Colm McGurk, were all drafted as Derry sought to put right the hurt of the previous two campaigns which had seen their rivals claim Sam Maguire on each occasion (Down 1991, Donegal 1992).

In his own mind, he was flying in training.

“(Before the Ulster semi-final) against Monaghan we trained on the Thursday night in Casement and I had been playing really well. We had played a practice match, which were bloody competitive games, in Glen on the Sunday and I scored five points from play. So I thought I was in with a good shout of playing against Monaghan.”

With the team announced following the Casement session, McCormick was disappointed not to be starting.

“I thought ‘at least I’m on the subs though’. So when Henry (Downey) told me in the car on the way home that I wasn’t in the six subs, I was dumbfounded,” he states.

“I got home that night and rang Eamonn Coleman to his house. The cheeky move that it was; I had a stand up row with him for half an hour on the phone. In his own inimitable way, Eamonn kept pushing me.

“Who should you be on for?” he kept asking. “Who do you think you should replace?”

I wouldn’t answer him. I told him that was his job. It was heated.

“Eamonn should have put the phone down on me in hindsight.

“But it just shows you: he was able to put all that aside for the greater good. He was prepared to take shit from a cheeky twenty-one-year-old, who he probably should have told where to go.

“Instead he listened to my reasoning, or attempted reasoning, about where I should be playing and why. He could obviously tell that I was exceptionally disappointed.”

Disappointed he may have been, but having learned the lesson from two years previous, McCormick stuck with it.

“We had a team meal in the Imperial hotel in Garvagh the following night (Friday) and he came over and reached down to the table and said “MA-CORMAN-ICK, you’re on the subs.”

The measure of the man began to sink in.

“He had gone back on his plans, whatever they were,” states McCormick.

With Down decimated in Newry in the previous round, Derry were slow to get out of the blocks at Casement Park, so Coleman decided to make changes at half time. McCormick got the nod.

“I went out and actually had a good second half as I was right up for it,” recalls McCormick. “I then played the Ulster final and unfortunately I played complete junk. How he didn’t take me off, I don’t know. Conditions were terrible but that wasn’t an excuse. I just didn’t play well. Whether I rested on my laurels from the Monaghan game, I don’t know, but I was poor.

“That was me then for the rest of the year. I didn’t feature in the All-Ireland semi-final or final. Eamonn seemed to just take a notion and that was it. I wasn’t sure how I stood with him.”

With Sam Maguire paraded through Maghera one late, late Monday night in September, the county was propelled into a dream-like state which would linger for some time. However, McCormick’s uncertainly over his own inter-county career continued.

“We went to Tenerife on a team holiday for two weeks and what happened on that holiday with Eamonn and me, I do not know, but we just seemed to get to know each other. It wasn’t that we were out together or anything, it was just sitting around communally, talking.

“I played every single game in 1994 in all competitions. Something happened in the period where he got a handle on me and I got a handle on him. I probably wasn’t the easiest person to manage but (after all that had happened) I had a complete appreciation about what Eamonn Coleman brought to Derry.”

When the All-Ireland champions hosted Dublin at a thronged Bellaghy in the league, McCormick found himself in an unusual position:

“1994 started with (Eamonn’s) hair brain notion of playing me fullback which worked for a game or two, but as soon as my man scored a goal or two against Westmeath, that was the end of that. I was back in the half forward line,” he explains.

After a gutting defeat to eventual All-Ireland champions, Down, in Celtic Park in 1994 – a game which Brian McCormick started – Derry’s dreams lay in ruins. However, Coleman had already begun to re-plan.

The ‘MA-CORMAN-ICK’ mode of address had now been replaced with the softer ‘Brian’, as the Lavey man recalls:

“On the way home from the Down game, Eamonn came down the bus and said to me: “Brian, you’ve made your way onto this team now and I want to see you cement your place for the future. This is the start of your Derry career.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

SMALL THINGS

Like some of the stories surrounding Sonny McCann’s legendary dead ball striking, context can be personal and time can alter perception. Events which happen can often get retold and reimagined. But not for McCormick.

“People need to remember that our All-Ireland win was in 1991,” he begins. “No-one had gone on to win an All-Ireland with Derry. John McGurk had no All-Star. Henry hadn’t captained Derry to the All-Ireland. We were all in the same boat and we all made our way with that team,” he says.

“We were also lucky with injuries that year,” he adds. “I don’t know how many we had, but there weren’t that many subs used.”

At 42 years-of-age, Anthony McGurk – a former double All-Star footballer – was certainly the eldest sub used, and to great effect. A titanic All-Ireland quarter-final battle at Ballinascreen was only eventually resolved in extra time after the eldest McGurk brother came off the bench to wade through the clabbery goalmouth and bundle over a decisive goal to force the additional twenty minutes. McGurk had clawed Lavey back from the edge of the abyss against a star-studded Tir Chonaill Gaels side featuring James McCartan and Mattie McGleenan. They didn’t look back.

Mary K Burke

It’s a cliché often trotted out, but to this day the whole campaign had been a team effort from beginning to end, in McCormick’s mind.

“Fergal Rafferty had been working in Dublin so couldn’t get to training much,” recalls McCormick. “He was very strong, a good runner, very competitive and very determined. He was a very important cog in the wheel, as everyone was.”

For someone who doesn’t watch DVDs back all that much, there is one particular sixty minutes of football that he sees time after time and whether he likes it or not.

“Lavey v Moortown, in the Ulster club of 1992 at Ballinascreen was a horrible game,” states McCormick. “It’s one which Fionn has gotten his hands on and subjects me to.”

McCormick’s five-year-old son couldn’t have finer examples to school with. Replaying the tape now in his own mind, McCormick is able to paint a wider picture.

“There’s Damian O’Boyle and James Chivers in the middle of the field and not many would fancy an hour following those two. Their work rate was phenomenal and James seemed to always pop up with a point from play as well,” he says.

“I was absolutely terrible that day but our defence got us through. The thing which always strikes me thinking back is how ferocious our boys were in their tackling. Damian Doherty, Ciarán McGurk, Henry Downey and Johnny weren’t big men, but they fought like tigers; so too Anthony Scullion, another leader (and captain of the Ulster champions of 1992).”

“But the standout moment for me was Brian Scullion. He’s there (on the video) making a run, which he has no need to be making, thirty-five yards across the pitch to someone else’s man and he then puts in one of his trademark flying blocks. It was just enough to put the fella off and he screwed his shot wide.”

Scullion’s actions had seen the Tyrone champions fail to gain parity with the game in the melting pot. Having put their bodies on the line, Lavey went on to win by two and would claim another Ulster senior title.

“It’s those small things which most people in the crowd don’t see or don’t care about – they’re the things that show the teams that are up for it and are determined to come out on top in the end,” declares McCormick.

Now that’s a fact.

Comments